Lawrence Bragg

Lawrence Bragg | |

|---|---|

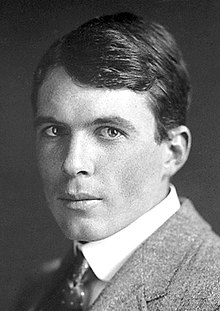

Bragg in 1915 | |

| Born | William Lawrence Bragg 31 March 1890 |

| Died | 1 July 1971 (aged 81) Waldringfield, Suffolk, England |

| Education | St Peter's College, Adelaide |

| Alma mater | University of Adelaide Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Known for | |

| Spouse |

Alice Hopkinson (m. 1921) |

| Father | William Henry Bragg |

| Relatives | Charles Todd (grandfather) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Academic advisors | J. J. Thomson William Henry Bragg |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students | William Cochran |

| 5th Cavendish Professor of Physics | |

| In office 1938–1953 | |

| Preceded by | J. J. Thomson |

| Succeeded by | Nevill Francis Mott |

| 3rd Director of National Physical Laboratory | |

| In office 1937–1938 | |

| Preceded by | Frank Edward Smith (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Charles Galton Darwin |

Sir William Lawrence Bragg (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971), known as Lawrence Bragg, was an Australian-born British physicist and X-ray crystallographer, discoverer (1912) of Bragg's law of X-ray diffraction, which is basic for the determination of crystal structure. He was joint recipient (with his father, William Henry Bragg) of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915, "For their services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays";[4] an important step in the development of X-ray crystallography.[5]

Bragg was knighted in 1941.[4] As of 2024, he is the youngest ever Nobel laureate in physics, or in any science category, having received the award at the age of 25.[6] Bragg was the director of the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, when the discovery of the structure of DNA was reported by James D. Watson and Francis Crick in February 1953.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Bragg was born in Adelaide, South Australia to Sir William Henry Bragg (1862–1942),[7] Elder Professor of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Adelaide, and Gwendoline (1869–1929), daughter of Sir Charles Todd, government astronomer of South Australia.

In 1900, Bragg was a student at Queen's School, North Adelaide, followed by five years at St Peter's College, Adelaide. He went to the University of Adelaide at the age of 16 to study mathematics, chemistry and physics, graduating in 1908. In the same year his father accepted the Cavendish chair of physics at the University of Leeds, and brought the family to England. Bragg entered Trinity College, Cambridge in the autumn of 1909 and received a major scholarship in mathematics, despite taking the exam while in bed with pneumonia. After initially excelling in mathematics, he transferred to the physics course in the later years of his studies, and graduated with first class honours in 1911. In 1914 Bragg was elected to a Fellowship at Trinity College – a Fellowship at a Cambridge college involves the submission and defence of a thesis.[8][9]

Among Bragg's other interests was shell collecting; his personal collection amounted to specimens from some 500 species; all personally collected from South Australia. He discovered a new species of cuttlefish – Sepia braggi, named for him by Joseph Verco.[10]

Career

[edit]X-rays and the Bragg equation

[edit]The composition of X-rays was unknown, his father argued that X-rays are streams of particles, others argued that they are waves. Max von Laue directed an X-ray beam at a crystal in front of a photographic plate; alongside of the spot where the beam struck there were additional spots from deflected rays – hence X-rays are waves.[11] In 1912, as a first-year research student at Cambridge, W. L. Bragg, while strolling by the river, had the insight that crystals made from parallel sheets of atoms would not diffract X-ray beams that struck their surface at most angles because X-rays deflected by collisions with atoms would be out of phase, cancelling one another out. However, when the X-ray beam struck at an angle at which the distances it passed between atomic sheets in the crystal equalled the X-ray's wavelength then those deflected would be in phase and produce a spot on a nearby film. From this insight he wrote the simple Bragg equation that relates the wavelength of the X-ray and the distance between atomic sheets in a simple crystal to the angles at which an impinging X-ray beam would be reflected.

His father built an apparatus in which a crystal could be rotated to precise angles while measuring the energy of reflections. This enabled father and son to measure the distances between the atomic sheets in a number of simple crystals. They calculated the spacing of the atoms from the weight of the crystal and the Avogadro constant, which enabled them to measure the wavelengths of the X-rays produced by different metallic targets in the X-ray tubes. W. H. Bragg reported their results at meetings and in a paper, giving credit to "his son" (unnamed) for the equation, but not as a co-author, which gave his son "some heartaches", which he never overcame.[12]

Work on sound ranging

[edit]Bragg was commissioned early in World War I in the Royal Horse Artillery as a second lieutenant of the Leicestershire battery.[13] In 1915 he was seconded to the Royal Engineers to develop a method to localise enemy artillery from the boom of their firing.[14][15] On 2 September 1915 his brother was killed during the Gallipoli Campaign.[16] Shortly afterwards, he and his father were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. He was 25 years old and remains the youngest science laureate. The problem with sound ranging was that the heavy guns boomed at too low a frequency to be detected by a microphone. After months of frustrating failure he and his group devised a hot wire air wave detector that solved the problem. In this work he was aided by Charles Galton Darwin, William Sansome Tucker, Harold Roper Robinson, Edward Andrade[17] and Henry Harold Hemming. British sound ranging was very effective; there was a unit in every British Army and their system was adopted by the Americans when they entered the war. For his work during the war he was awarded the Military Cross[18] and appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire.[19] He was also Mentioned in Despatches on 16 June 1916, 4 January 1917 and 7 July 1919.[20][21][22]

Hot wire sound ranging was used in World War II during which he served as a civilian adviser.[23]

Between the wars, from 1919 to 1937, he worked at the Victoria University of Manchester as Langworthy Professor of Physics. He became the director of the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington in 1937.[24]

After World War II, Bragg returned to Cambridge, splitting the Cavendish Laboratory into research groups. He believed that "the ideal research unit is one of six to twelve scientists and a few assistants".

University of Manchester (1919–1937)

[edit]When demobilised he returned to crystallography at Cambridge. They had agreed that father would study organic crystals, son would investigate inorganic compounds.[1][4] In 1919 when Ernest Rutherford, a long-time family friend, moved to Cambridge, Lawrence Bragg replaced him as Langworthy Professor of Physics at the Victoria University of Manchester. He recruited an excellent faculty, including former sound rangers, but he believed that his knowledge of physics was weak and he had no classroom experience. The students, many veterans, were critical and rowdy. He was deeply shaken but with family support he pulled himself together and prevailed. He and R. W. James measured the absolute energy of reflected X-rays, which validated a formula derived by C. G. Darwin before the war.[25] Now they could determine the number of electrons in the reflecting targets, and they were able to decipher the structures of more complicated crystals like silicates. It was still difficult: requiring repeated guessing and retrying. In the late 1920s they eased the analysis by using Fourier transforms on the data.

In 1930, he became deeply disturbed while weighing a job offer from Imperial College, London. His family rallied around and he recovered his balance while they spent 1931 in Munich, where he did research.

National Physical Laboratory (1937–1938)

[edit]He became director of the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington in 1937,[24] bringing some co-workers along. However, administration and committees took much of his time away from the workbench.

University of Cambridge (1938–1954)

[edit]Rutherford died and the search committee named Lawrence Bragg as next in the line of the Cavendish Professors who direct the Cavendish Laboratory. The Laboratory had an eminent history in atomic physics and some members were wary of a crystallographer, which Bragg surmounted by even-handed administration. He worked on improving the interpretation of diffraction patterns. In the small crystallography group was a refugee research student without a mentor: Max Perutz. He showed Bragg X-ray diffraction data from haemoglobin, which suggested that the structure of giant biological molecules might be deciphered. Bragg appointed Perutz as his research assistant and within a few months obtained additional support with a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. The work was suspended during the Second World War when Perutz was interned as an enemy alien and then worked in military research.

During the war the Cavendish offered a shortened graduate course which emphasised the electronics needed for radar. Bragg worked on the structure of metals and consulted on sonar and sound ranging, for which the Tucker microphone was still used. Bragg was knighted and became Sir Lawrence in 1941. After his father died in 1942, Bragg served for six months as Scientific Liaison Officer to Canada. He also organised periodic conferences on X-ray analysis, which was widely used in military research.

After the war Bragg led in the formation of the International Union of Crystallography and was elected its first president. He reorganised the Cavendish into units to reflect his conviction that "the ideal research unit is one of six to twelve scientists and a few assistants, helped by one or more first-class instrument mechanics and a workshop in which the general run of apparatus can be constructed."[26] Senior members of staff now had offices, telephones, and secretarial support. The scope of the department was enlarged with a new unit on radio astronomy. Bragg's own work focused on the structure of metals, using both X-rays and the electron microscope. In 1947 he persuaded the Medical Research Council (MRC) to support what he described as the "gallant attempt"[27] to determine protein structure as the Laboratory of Molecular Biology, initially consisting of Perutz, John Kendrew and two assistants. Bragg worked with them and by 1960 they had resolved the structure of myoglobin to the atomic level.[28] After this Bragg was less involved; their analysis of haemoglobin was easier after they incorporated two mercury atoms as markers in each molecule. The first monumental triumph of the MRC was decoding the structure of DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick. Bragg announced the discovery at a Solvay conference on proteins in Belgium on 8 April 1953, though it went unreported by the press. He then gave a talk at Guy's Hospital Medical School in London on Thursday, 14 May 1953, which resulted in an article by Ritchie Calder in the News Chronicle of London on Friday, 15 May 1953, entitled "Why You Are You. Nearer Secret of Life". Bragg nominated Crick, Watson and Maurice Wilkins for the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine; Wilkins' share recognised the contribution of X-ray crystallographers at King's College London.[29] Among them was Rosalind Franklin, whose "photograph 51" showed that DNA was a double helix, not the triple helix that Linus Pauling had proposed. Franklin died before the prize (which only goes to living people) was awarded.

The Royal Institution (1954–1971)

[edit]In 1953 the Braggs moved into the elegant flat for the Resident Professor in the Royal Institution in London, the position his father had occupied when he died. In 1934 and 1961 Lawrence had delivered the Royal Institution Christmas Lecture and since 1938 he had been Professor of Natural Philosophy in the Institution, delivering an annual lecture. His father's successors had weakened the Institution, so Bragg had to rebuild it. He bolstered finances by enlisting corporate sponsors, the traditional Friday Evening Discourses were followed by a dinner party for the speaker and carefully selected possible patrons, more than 120 of them each year. "Two of these Discourses in 1965 gave him particular pleasure. On 7 May, Lady Bragg, who had been a member of the Royal Commission on Marriage and Divorce (1951–55) and was Chairman of the National Marriage Guidance Council, lectured on 'Changing patterns in marriage and divorce'; and on 15 November, Bragg listened with evident pride to the Discourse on 'Oscillations and noise in jet engines' given by his engineer-son Stephen, who was then Chief Scientist at Rolls-Royce Ltd and later became Vice-Chancellor of Brunel University."[30] He also introduced a programme of highly regarded Schools' Lectures, enlivened by the elaborate demonstrations that were a hallmark of the Institution. He gave three of these lectures on "electricity".[31]

He continued research in the Institution by recruiting a small group to work in the Davy-Faraday Laboratory in the basement and in the adjoining house, supported by grants he obtained. A visitor to the laboratory succeeded in inserting heavy metals into the enzyme lysozyme; the structure of its crystal was solved in 1965 at the Royal Institution by D. C. Phillips and his coworkers, with the computations on the 9,040 reflections performed on the digital computer at the University of London, which greatly facilitated the work.[32] Two of the illustrations of the positioning of amino acids in the chain were drawn by Bragg. Unlike myoglobin, in which nearly 80 per cent of the amino-acid residues are in the alpha-helix conformation, in lysozyme the alpha-helix content is only about 40 per cent of the amino-acid residues found in four main stretches. Other stretches are of the 310 helix, a conformation that they had proposed earlier.[33] In this conformation, every third peptide is hydrogen-bonded back to the first peptide, thus forming a ring containing ten atoms. They had the complete structure of an enzyme in time for Bragg's 75th birthday. He became Professor Emeritus in 1966.

X-ray analysis of protein structure flourished in subsequent years, determining the structures of scores of proteins in laboratories around the world. Twenty eight Nobel Prizes have been awarded for work using X-ray analysis. The disadvantage of the method is that it must be done on crystals, which precludes seeing changes in shape when enzymes bind substrates and the like. This problem was solved by the development of another line Bragg had initiated, using modified electron microscopes to image single frozen molecules: cryo-electron microscopy.[34]

In his long association with the Royal Institution he was:

- Professor of Natural Philosophy, 1938–1953

- Fullerian Professor of Chemistry, 1954–1966

- Superintendent of the House, 1954–1966

- Director of the Davy-Faraday Research Laboratory, 1954–1966

- Director of the Royal Institution, 1965–1966

- Emeritus Professor, 1966–1971

Personal life

[edit]In 1921 he married Alice Hopkinson (1899–1989), a cousin of a Cecil Hopkinson (1891–1917) who shared rooms with Bragg, and was one of his closest friends whilst they were both studying at Cambridge.[35][36] Cecil was the son of John Hopkinson who was Alice's uncle.

They had four children, the engineer Stephen Lawrence (1923–2014), David William (1926–2005), Margaret Alice (1931–2022) (who married the diplomat Mark Heath), and Patience Mary (1935–2020) (who married David, the son of Sir George Thomson the Nobel prize winning physicist[37]). Alice was on the staff at Withington Girls' School until Bragg was appointed director of the National Physical Laboratory in 1937.[24] She was active in a number of public bodies and served as Mayor of Cambridge from 1945 to 1946.

Bragg's hobbies included drawing – family letters were illustrated with lively sketches – painting, literature and a lifelong interest in gardening.[38] When he moved to London, he missed having a garden and so worked as a part-time gardener, unrecognised by his employer, until a guest at the house expressed surprise at seeing him there.[39] He died at a hospital near his home at Waldringfield, Ipswich, Suffolk. He was buried in Trinity College, Cambridge; his son David is buried in the Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge, his grave is within a few paces of that of Bragg's close friend, Rudolph Cecil Hopkinson, who incurred a severe head wound in the 1914–19 war and died a few months after being invalided back to the UK.[37]

In August 2013, Bragg's relative, the broadcaster Melvyn Bragg, presented a BBC Radio 4 programme ("Bragg on the Braggs") on the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics winners.[40][41]

Honours and awards

[edit]

Bragg was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1921[1] – "a qualification that makes other ones irrelevant".[42] He was knighted by King George VI in the 1941 New Year Honours,[43] and received both the Copley Medal and the Royal Medal of the Royal Society. Although Graeme Hunter, in his book on Bragg Light is a Messenger, argued that he was more a crystallographer than a physicist, Bragg's lifelong activity showed otherwise—he was more of a physicist than anything else. Thus, from 1939 to 1943, he served as President of the Institute of Physics, London.[8] In the 1967 New Year Honours he was appointed Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour by Queen Elizabeth II.[44]

Since 1967 the Institute of Physics has awarded the Lawrence Bragg Medal and Prize. Additionally since 1992, the Australian Institute of Physics has awarded the Bragg Gold Medal for Excellence in Physics[45] to commemorate Lawrence Bragg (in front on the medal) and his father, William Bragg, for the best PhD thesis by a student at an Australian university.

- Nobel Prize (1915)

- Matteucci Medal (1915)

- Hughes Medal (1931)

- Royal Medal (1946)

- Guthrie Lecture (1952)

- Copley Medal (1966)

The Electoral district of Bragg, in the South Australian House of Assembly, was created in 1970, and was named after both William and Lawrence Bragg.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Phillips, D. (1979). "William Lawrence Bragg. 31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 25: 74–143. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1979.0003. JSTOR 769842.

- ^ "Alexander Stokes". The Telegraph. 28 February 2003. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "National Library of Wales: From Warfare to Welfare 1939–59". Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ a b c "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1915". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Stoddart, Charlotte (1 March 2022). "Structural biology: How proteins got their close-up". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-022822-1. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Facts on the Nobel Prize in Physics". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (23 September 2004). "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. ref:odnb/30845. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30845. Retrieved 29 December 2019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b "Cambridge Physicists - William Lawrence Bragg". Cambridge Physics. Cavendish Laboratory. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ See Fred Hoyle's remarks regarding Hutchinson in 1965 Galaxies, Nuclei and Quasars p. 38 London: Heinemann; and R. J. N. Phillips 1987, "Some Words from a Former Student", in Tribute to Paul Dirac, Bristol: Adam Hilger, p. 31.

- ^ Jenkin, John William and Lawrence Bragg; Father and Son. Oxford University Press 2008 ISBN 978 0 19 923520 9

- ^ Laue, Max von. "Concerning the Detection of X-ray Interferences". Nobel Prizes. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Van der Kloot, William (2014). Great Scientists wage the Great War. Stroud: Fonthill. p. 129.

- ^ "No. 28879". The London Gazette. 25 August 1914. p. 6702.

- ^ William Van der Kloot, Lawrence Bragg's role in the development of sound-ranging in World War I, Notes and Records of the Royal Society, 22 September 2005, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 273–284.

- ^ Van der Kloot 2014, pp. 129–161.

- ^ "Casualty Details: Bragg, Robert Charles". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ Cottrell, A. (1972). "Edward Neville da Costa Andrade. 1887–1971". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 18: 1–20. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1972.0001.

- ^ "No. 30450". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1918. p. 32. MC

- ^ "No. 30576". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 March 1918. p. 3289. OBE

- ^ "No. 29623". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 June 1916. p. 5930. mid

- ^ "No. 29890". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 January 1917. p. 207. mid

- ^ "No. 31437". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 July 1919. p. 8523. mid

- ^ Van der Kloot 2014, pp. 207–208.

- ^ a b c Newsletter 1936–1937. Withington Girls' School. 1937.

- ^ Bragg, W. Lawrence (1965). "Reginald William James. 1891–1964". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 11: 114–125. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1965.0007. JSTOR 769264.

- ^ Phillips 1979, p. 117.

- ^ Phillips 1979, p.118

- ^ Bragg, Sir Lawrence; J. C. Kendrew; M. F. Perutz (1950). "Polypeptide chain configurations in crystalline proteins". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 203 (1074): 321–357. Bibcode:1950RSPSA.203..321B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1950.0142. S2CID 93804323.

- ^ "Maurice Wilkins – Facts". Nobel Prize. Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Phillips 1979 ,p.126.

- ^ "William Lawrence Bragg (1890–1971)".

- ^ Blake, C. C. F.; D. F. Koenig; G. A. Mair; A. C. T. North; D. C. Phillips; V. R. Sarma (1965). "Structure of egg-white lysozome". Nature. 206 (4986): 757–761. Bibcode:1965Natur.206..757B. doi:10.1038/206757a0. PMID 5891407. S2CID 4161467.

- ^ Bragg et al. 1950.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2017".

- ^ Glazer, A. M.; Thomson, Patience (2015). Crystal Clear: The Autobiographies of Sir Lawrence & Lady Bragg. doi:10.1063/PT.3.3270. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Edge, David (20 June 1969). "Oral History: William Lawrence Bragg". American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b Chorley, Katharine (2001). "Foreword". Manchester Made Them. Silk Press Ltd. p. 5. ISBN 978-1902685090.

- ^ Thomson, Patience (2013). "A tribute to W. L. Bragg by his younger daughter" (PDF). Acta Crystallographica Section A. A69 (Pt 1): 5–7. Bibcode:2013AcCrA..69....5T. doi:10.1107/S0108767312047514. PMID 23250053. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Crick, Francis (1989). What Mad Pursuit. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 53. ISBN 978-0140119732.

- ^ "Bragg on the Braggs". 2 March 2017.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Bragg on the Braggs".

- ^ G. K. Hunter 2004 Light is a Messenger Oxford: OUP.

- ^ "No. 35029". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1940. p. 1. Knight bachelor

- ^ "No. 44210". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 1966. p. 26. CH

- ^ Bragg Gold Medal for Excellence in Physics Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]- Hunter, Graeme (2004). Light Is A Messenger, the Life and Science of William Lawrence Bragg. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852921-X.

- Finch, John (2008). A Nobel Fellow On Every Floor. Medical Research Council. ISBN 978-1-84046-940-0. (This book is about the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge.)

- Ridley, Matt (2006). Francis Crick: Discoverer of the Genetic Code. Eminent Lives. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-082333-X.

- Jenkin, John (2008). William and Lawrence Bragg, Father and Son: The Most Extraordinary Collaboration in Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

External links

[edit] Media related to William Lawrence Bragg at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Lawrence Bragg at Wikimedia Commons- First press stories on DNA

- Nobelprize.org – The Nobel Prize for Physics in 1915

- Lawrence Bragg on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, September 6, 1922 The Diffraction of X-Rays by Crystals

- A collection of digitised materials related to Bragg's and Linus Pauling's structural chemistry research.

- Key Participants: Sir William Lawrence Bragg – Linus Pauling and the Race for DNA: A Documentary History

- NOVA Episode on Photograph 51

- Oral History interview transcript with William Lawrence Bragg on 20 June 1969, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

- Bragg, Lawrence (Sir) (1890–1971) National Library of Australia, Trove, People and Organisation record for William Lawrence Bragg

- The Nature of Things: Oil, Soap and Detergent, Ri Channel video, November 1959

- The Nature of Things: Atoms and Molecules, Ri Channel video, October 1959

- The Nature of Things: Solids, Liquids and Gases, Ri Channel video, November 1959

- Portraits of Lawrence Bragg at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- 1890 births

- 1971 deaths

- Military personnel from Adelaide

- British Army personnel of World War I

- Royal Horse Artillery officers

- 20th-century British physicists

- Academics of the Victoria University of Manchester

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Australian Nobel laureates

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- Australian people of English descent

- 20th-century Australian physicists

- Experimental physicists

- Optical physicists

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Australian Knights Bachelor

- Australian Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Australian Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- Scientists from Adelaide

- Scientists from Ipswich

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Australian recipients of the Military Cross

- Royal Medal winners

- University of Adelaide alumni

- People educated at St Peter's College, Adelaide

- Presidents of the Institute of Physics

- X-ray crystallography

- British crystallographers

- English Nobel laureates

- British Nobel laureates

- Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Foreign fellows of the Indian National Science Academy

- Directors of the National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom)

- Directors of the Royal Institution

- Members of the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin

- Leeds Blue Plaques

- Recipients of the Matteucci Medal

- Recipients of the Dalton Medal

- Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society

- Cavendish Professors of Physics

- Presidents of the International Union of Crystallography

- Members of the American Philosophical Society